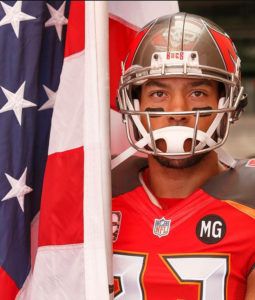

Vincent Jackson is probably known to most as a former Tampa Bay Buccaneers wide receiver.

What they may not know is that he owns five restaurants. Two in San Diego, one in Las Vegas, Cask Social Kitchen in Tampa and now his passion project, the Historic Manhattan Casino in St. Petersburg.

He is also co-founder of CTV Capital, a real estate, development and private equity firm that has completed development of more than $100 million, since 2014, in Florida.

And if that’s not enough to keep him busy, he also runs Jackson in Action, a nonprofit foundation that supports families in the military.

An only child of two military parents himself, it’s a project near and dear to his heart and one in which he is heavily involved.

“The emails come to me, my wife, or one of the few people who help me run it. We are a hands-on group,” says Jackson, in his office, located in Ybor City.

The interview occurred in June, when COVID-19 numbers started picking up again and sports seasons were still in limbo.

“This thing is crazy, every time we take two steps forward, it’s eight steps back,” Jackson says. “I watch European soccer, I watch tennis and I watch baseball. I follow all sports, and I have been trying to see how different industries, and different leagues, are coming back and [positive COVID-19 cases] are still just popping. So it’s just going to be a challenge. I don’t know if [the football season] could, or should, happen. But it would be the most Tampa Bay thing to happen to us.”

Jackson is referring to the excitement, albeit brief, that Tom Brady and Rob Gronkowski brought to the franchise earlier in the year. It was a short-lived distraction from the spread of the coronavirus. At the time of press, it still wasn’t determined what a fall football season would look like or if it even will happen.

“But what’s more important on a global aspect with the things that are going on in the world right now, I hate to say it, but it would need to take a back seat,” Jackson says. “Even if they don’t put fans in the stands, which is what they’re doing with soccer right now overseas, they’re just playing games … but at the end of the day there are trainers and coaches and then, the exponential effect of their families … getting together and doing it together in stadiums this year? I don’t see that happening.”

A MILITARY CHILD

Jackson admits, like everyone else, 2020 has been a roller coaster and everyone is just navigating the best anyone can.

But, thanks to his early life, he feels he learned how to be nimble.

Jackson was born in January 1983, in Louisiana, and lived there until he was about 6 years old. Being a military kid, his father worked in the infirmary and his mother often worked on the military base, Jackson moved around quite a bit as a youngster.

“It’s part of the military lifestyle of just picking up and going to a new state and new school,” he says. “It’s not the easiest thing to go through, but it was a part of building my resilience and my ability to adapt, and adjust, in different, challenging environments.”

His family also spent three years in Germany.

“I absolutely love Europe,” Jackson says. “It really opened my eyes to how people on the other side of the world live.”

From there, his family was set to relocate to Hawaii which delighted Jackson. He envisioned himself learning how to surf.

“We literally sent everything over. All of our furniture and even our dog,” Jackson says.

Two weeks before the family was set to move to the island in the Pacific, they received notice that instead of sunny beaches they were headed to the mountains of Colorado.

“My parents were a great example for me. We don’t complain. This is what we’ve been asked to do,” Jackson says. “It was a great opportunity for my father to go to Colorado Springs and take a really strong position.”

Neither of Jackson’s parents went to college straight out of high school and both were from rougher areas. Jackson’s father, Terence, was from Detroit, and his mother, Sherry, was from Mercer, Pennsylvania.

Jackson’s father wanted to get out of Detroit, and the military provided that opportunity.

“It was amazing to watch them be so adaptive, and so progressive, for themselves as professionals and to what they built from where they came from, which wasn’t very much, to give us a middle-class life,” Jackson says.

Jackson proudly shares that both eventually returned to college in their adult years to earn their degrees.

“Education was always a priority in our home. I graduated high school with a 4.1 GPA. My parents were a great example of work ethic and they instilled that education was what would carry you in life,” Jackson says. “Sports was not something that I ever felt was going to be my boat. I didn’t know it would [be a career] until my junior year of college.”

Jackson had two options for college that couldn’t be more different. Columbia University, in New York, or the University of Northern Colorado.

At Northern Colorado Jackson would remain closer to home, and family, and would be eligible for state scholarships, some for sports and some for his impressive academic accomplishments.

At Columbia, he would move across the country to a new, and sometimes-intimidating, city, and know no one.

Jackson decided to stay in the mountains. He started school in fall 2001 and says he’s fully aware that life could have been very different had he moved to New York.

Colorado Springs wasn’t known as being a powerhouse community for churning out football players.

“I didn’t get to play in all-star games. I was good statistically and I had good measurables physically. I was a good athlete, but I wasn’t on the regional radar for large colleges,” Jackson says. “At the end of the day, I went home and it was homework and school, as usual for my family.”

Jackson wasn’t tailored to be a professional athlete. His parents would sign him up for any seasonal sport to keep him busy.

Jackson attended the University of Northern Colorado for 3½ years, with a focus on business studies, when an opportunity arrived that would pull him into the wide world of professional sports and away from finishing his degree, at that time.

THE ROAD TO TAMPA

Jackson traveled down to Tucson, Arizona, to train at Fischer Sports Institute, and later was the second-round draft pick for the San Diego Chargers, in 2005. He played seven years with the team before signing with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in 2012.

“I was blessed. I went from the beaches of San Diego to the beaches of Tampa Bay,” Jackson says with a laugh.

While in Tampa, Jackson finished his degree at the University of South Florida in business management.

“I’m a lifetime learner,” Jackson says. “Academics has always been my rock.”

While the flashy part of Jackson’s career might have been on the football field, he always came back to his interest in business, and having endeavors off the field, that would provide a career when the roars from football fans stopped.

“I was still playing full-time football. It was maybe my third year with the NFL when I started noticing that every time I came back for training camp, there would be five new guys and 10 more guys gone,” Jackson says. “It’s a revolving door. It’s a very competitive industry. People get hurt, coaches change and players are coming and going all the time.”

Jackson decided he could use his smarts, and connections, to set up the post-football career plan.

“I said, ‘You know what? I’m not going to be caught off guard. I have my education; I feel like I’m a pretty smart young man. I’m going to invest in myself, and my time, and use my platform to go out there in the community,” he says.

Starting in his third year in the NFL, he started asking “civilian” professionals he’d meet to, essentially, shadow them and spend some time in their offices, to do what he’s always done best: learn.

“I just wanted to pick their brains and understand their outlook and successful ventures,” he says.

Some of his first business ventures were restaurants, as some of his first experiences of earning a paycheck were in the food industry, it was an intuitive transition for him.

He established two original-concept restaurants, in San Diego, and one franchise in Las Vegas, the Tilted Kilt.

“I like to create the concepts, and be a part of the design, but I knew that I was not one to actually run the restaurant, operationally,” he says. “You have to have amazing people operating a restaurant.”

He started to also move into real estate, and philanthropy, which he says is something that he was always passionate about.

When he was 6 or 7 and still living in Germany with his family, Jackson’s father would take him to volunteer a few times every month. Supporting those less fortunate was a responsibility taught at a young age. Whether it was cleaning up a highway or pouring soup at the Salvation Army, it was important to give back to the community, he says.

His current corporate entity, CTV Capital, now helps him do it in a new way. The company invests in homes and properties and provides capital for projects, sometimes even providing value to an existing community.

“I can take a house, or a family, and give them an opportunity for financing and homeownership, and sometimes we can improve the value of a neighborhood,” Jackson says.

While trying to establish some of his business ventures, he says there was the athlete stereotype he had to contend with.

“That’s a challenge I think all athletes face,” Jackson says. “People think we are all multi-millionaires.”

He notes that, yes, athletes are paid well in exchange for the talents and the grueling, sometimes-dangerous body damage they endure, and notes he gets that is the trade.

“I do want people to know those statistics you see about why athletes go broke, there’s a reason for that and it’s education,” he says. “When young, talented athletes are pushed through secondary education, that values athletic performance, that can happen.”

CTV Capital was established in 2012 by Jackson, and two other investors, focused on real estate investment projects. Jackson relocated the office to Ybor City in 2014.

Jackson met his wife, Lindsey, in San Diego. They’ve been together for 12 years, and married for nine years, and have four children together. His oldest is 6 years old, and his youngest is 19 months.

“Being a dad is the best job in the world,” Jackson says.

He loves the Tampa Bay area and has made efforts to plant roots here.

What initially impressed him was the neighbors that came by to welcome him to the neighborhood. Most, at least, seemed as if they had no idea he was a football player.

“Is this real southern hospitality that I see on TV? Is this real?” he says with a laugh. “They don’t care about what you do for a living, they care about you as a human being. Nothing against California. I love California. I still have businesses out there. San Diego is a beautiful city, most of California is. But I lived in that house [in San Diego], and I think I met two neighbors in six years.”

He knew he wanted to start a foundation and felt that Tampa was the place he could do that.

“I didn’t start a foundation out there because I wasn’t ready. I didn’t have the people around me or feel confident enough to take that responsibility on and put my name on something. I didn’t know if I would always be there.”

JACKSON IN ACTION

The mission of the Jackson in Action 83 Foundation is to provide support to military families focusing on the educational, emotional and physical health of the children.

“There’s a lot of people doing work to help to improve and accelerate the areas of concern in our community,” Jackson says. “Our foundation is a niche. We focus on military families.”

“Our day-to-day programming is where we can truly make a difference and impact 300 kids or 350 families.”

One of the issues the foundation seeks to help with is the issues that arise with spouses, and families, having to move frequently in the military.

“As a kid, I had to move three times in elementary school,” Jackson says. “When we moved to Arizona, I had to do my whole second grade again because they didn’t take my transcripts from Louisiana. I was spending 10 hours a day at school to get caught up.”

Jackson and his wife, who is an elementary educator, have co-written children’s books to help kids they work with.

“This foundation started as a way to give back to the community and use the NFL platform to spread goodness to Tampa, but it has turned into so much more than that for us,” says Lindsey Jackson.

With social distancing during COVID-19, it’s made the work they do more challenging.

He mentions the annual baby shower the foundation holds which is a huge celebration in a ballroom with food and gifts. He says this year it might look different and be held as a drive-through.

“I had six pallets of cribs dropped off at my home,” Jackson says. “We’re going to find a way to do something.”

The Jacksons pass their philanthropic nature down to their children.

“I take them to places and tell them, we’re going to help feed some folks,” he says.

“My wife and I come from the same type of background and pass on to them, it’s an attitude of gratitude.”

During the Black Lives Matters movement, Jackson says he’s tried to have conversations with his eldest children about the world they are currently living in. And some of his views have evolved, as well.

“When it started a few years ago, at that point in time, with my family’s background with the military and my reverence for veterans and people that made the ultimate sacrifice … I couldn’t affirm that I would take a knee,” Jackson says. “I respect the cause and I respect their ability to do so. I felt there was nothing wrong with them doing it, but would I do it myself? But I now understand it’s a platform for these athletes, or anyone professionally. Your platform is your platform for whatever you can do to get your message heard.”

Jackson says he’s proud of his country and grateful to people having hard conversations about race and inequality.

“For the people that are standing up and willing to put a lot on the line to get this message out. They’re coming from all different walks of life,” he says. “I think that systemic issues have got to be addressed. I’m so glad we’re finally having the hard conversations. It’s uncomfortable and it’s going to be uncomfortable for a while. But we get to be a part of a generation that is going to be in social studies books for future generations. Our kids, and our kids’ kids, are going to go ‘Wow, you guys had to go through BLM? What was that like?’ This is just as impactful as things that happened in the ‘60s.”

Jackson is clear that he doesn’t condone criminal activity, noting that it harms the movement.

“The people that are doing it peacefully and using the platforms and going up the methodical way of reaching the right people and getting into the right ears, that’s the way it’s going to be done. It has to be done that way,” he says. “We’re in the thick of it right now. Time will tell how Tampa, and our nation, adjusts itself and reforms itself.”

Jackson retired from the NFL in 2017 and opened Cask, in Tampa, along with his partner Adam Itzkowitz, in 2015.

His latest project is the Historic Manhattan Casino, which is now going on for two years this winter.

Built in 1925, the Manhattan Casino is revered as significant for its contribution to entertainment, and the culture, in the African American community. Some of American music’s most legendary performers played at the Manhattan including James Brown, Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, Ray Charles and Nat “King” Cole. The venue closed its doors in 1968, but Jackson is confident it will be a fixture for the community for years to come.

Callaloo is still operating at the Manhattan Casino, which is operated by the Callaloo Group, consisting of partners Ramon Hernandez and Mario Farias. But the downtime during the pandemic has created some breathing room to plan for the project’s continued progress.

“We’ve been using this time with COVID as a restart button, I’m excited about it. I think the city is ready for the resurgence of this facility with new partner, Rising Tides,” he says. ♦

BEHIND THE SCENES PHOTOS

[image_slider_no_space on_click=”prettyphoto” height=”300″ images=”10910,10911,10912,10913,10914,10915,10916″]

Awesome article and insight into a great man and friend, and of course, well done by the TBBW Team.

Vincent Jackson is such a class act.

What a great article this is a inspirational young man. That aside how is that I have so much in common with this person and I’ve never met him

Excellent, inspirational read. Thank you TBBW!

I am very proud of the examples you are setting. God bless you and your family.