Gasparilla is often treated like a relic. A pirate myth that Tampa pulls out once a year for a parade, a party and a long weekend.

Its history is more deliberate than that.

What began in the early 1900s as a civic marketing play sharpened by newspaper hype and social club theater evolved into one of the most durable identity engines the city has ever built.

Over time, Gasparilla became less about the pirate and more about how Tampa learned to tell its own story.

That philosophy still shapes the city today.

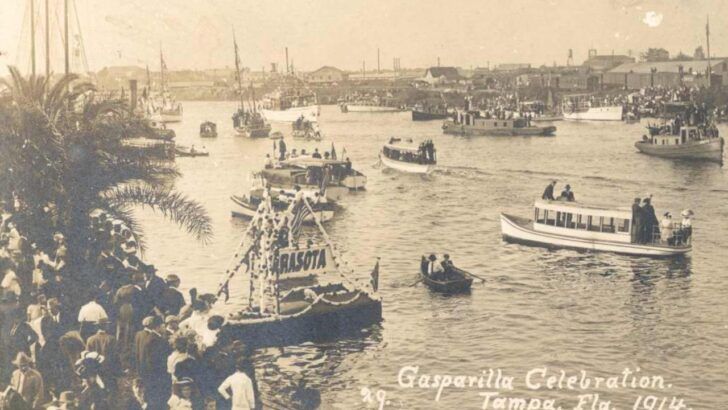

“The parade itself has its origins in 1904,” said Rodney Kite-Powell, historian at the Tampa Bay History Center. “It was when Louise Francis Dodge wanted to liven up the annual May Day parade.”

Dodge’s collaborator was George Hardee, an Army Corps of Engineers officer from New Orleans who understood spectacle and how quickly it could spread.

“He suggested some kind of Mardi Gras type celebration,” Kite-Powell said, “but kind of with a twist.”

That twist was a pirate.

A story built on spectacle

Hardee had spent time around Charlotte Harbor and had heard stories about a legendary figure who later became the character known as Gasparilla.

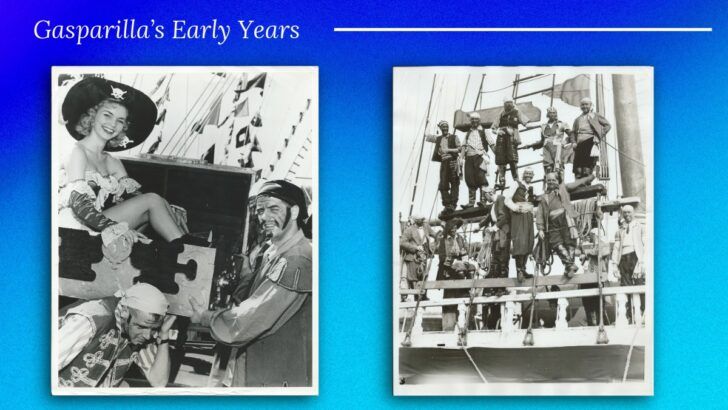

Early organizers did not treat the idea as folklore. They treated it as theater.

“Why don’t you have some prominent young men from Tampa from the social club head it up,” Kite-Powell said, “and we can invade your parade, basically.”

The first invasion arrived on horseback, folded into the existing May Day celebration. Newspapers treated it like a developing story rather than a single event.

READ: TAMPA BAY BUSINESS NEWS

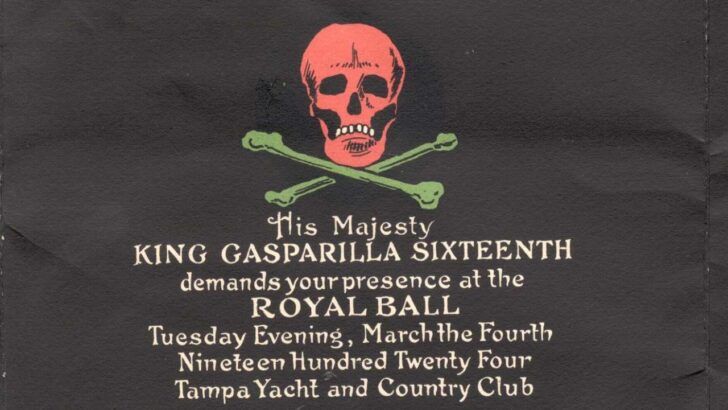

Days before the parade, the Tampa Tribune published reports about a mysterious pirate ship just offshore, complete with messages from King Gasparilla.

The city played along.

Gasparilla continued in fits and starts over the following years, tied at times to other celebrations before organizers committed to making it its own annual anchor.

“By 1912, they had the first kind of Gasparilla that existed just for its own purposes of being Gasparilla,” Kite-Powell said.

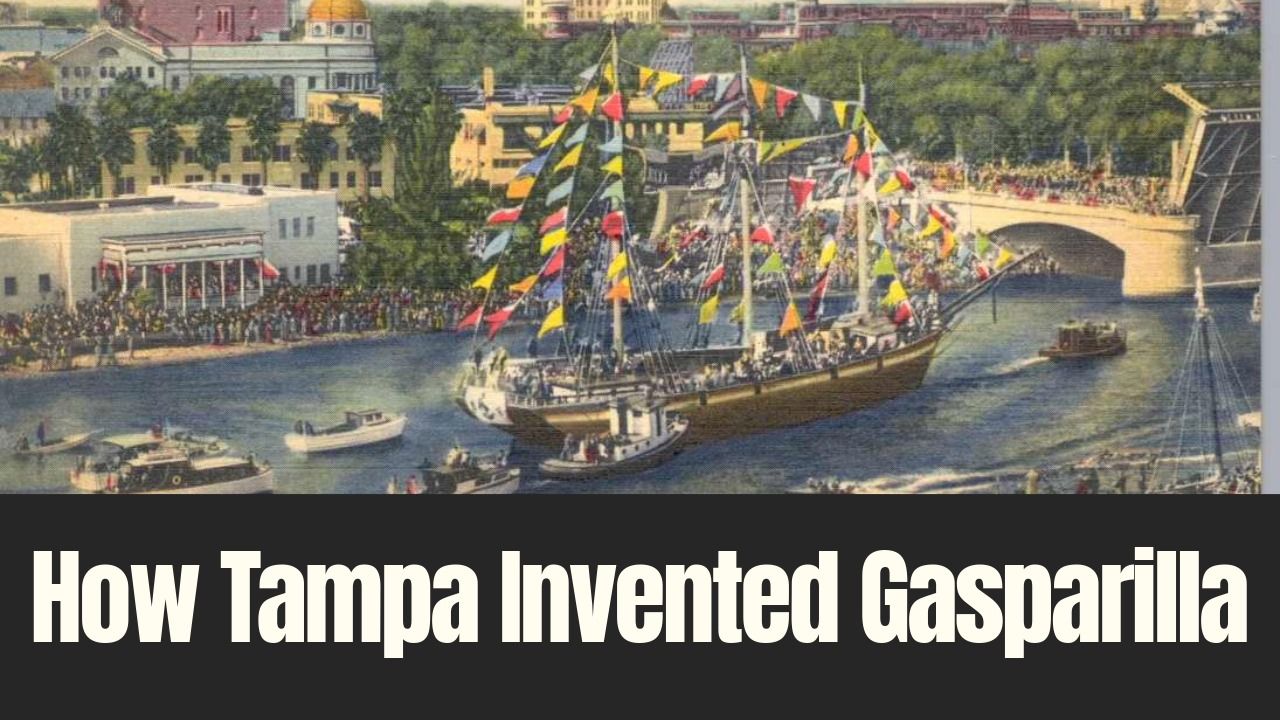

When the ship made it permanent

If 1904 created the idea, 1911 made it unforgettable.

“They began invading by ship in 1911,” Kite-Powell said.

That decision locked in the elements that people still recognize today.

Pirates parading through the streets. Cannon fire and gunfire. Coins and throws for the crowd. Even the flotilla of private boats crowding the channel during the invasion appears in early photographs.

“A lot of the things that happen today with the Gasparilla parade are things that have happened for over 100 years,” Kite-Powell said.

What changed over time was not the concept but the execution.

READ: TAMPA RETAIL & HOSPITALITY NEWS

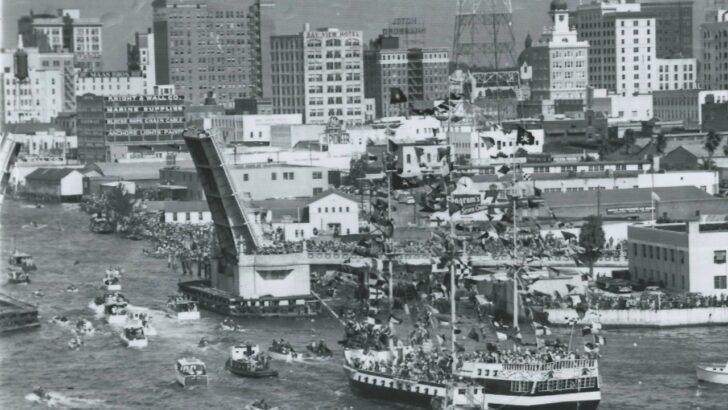

For decades, the ship traveled up the Hillsborough River and docked near what is now the University of Tampa or farther north near today’s Armature Works.

That shifted when the Lee Roy Selmon Expressway was built and the ship’s masts could no longer clear the bridge.

The ship itself evolved, too. The crew acquired its first owned vessel in the 1940s, followed by the current ship, which began sailing in 1954.

Early operations were not always smooth.

“It took a few years before they realized that they couldn’t allow the pirates to actually navigate their own ship,” Kite-Powell said. “They would run aground. They were drunk and they didn’t know what they were doing.”

Today, the invasion is tightly controlled, operated by tugboats with sober crews and maritime professionals.

“It’s executed incredibly well now,” he said.

What people think is timeless often is not

Many spectators associate Gasparilla with beads, but that tradition is relatively new.

“Beads were introduced in the mid to late 1980s,” Kite-Powell said.

Even that origin is disputed. The first bead year coincided with a parade nearly washed out by rain, leaving little documentation beyond anecdote.

READ: TAMPA BAY REAL ESTATE NEWS

“All the coverage in the paper was about the rain,” Kite-Powell said. “So it’s hard to really track down that.”

The takeaway is not trivial. Gasparilla’s most recognizable elements are layered atop older rituals. What feels eternal is often adaptive.

A parade shaped by infrastructure

Ask longtime residents where Gasparilla begins and most will say Bayshore Boulevard.

Historically, that was not the case.

“For the first 50-plus years of the parade, it was never even on Bayshore,” Kite-Powell said.

The parade originally centered on downtown and ended at the old fairgrounds near Plant Hall.

READ: DOWNTOWN TAMPA DEVELOPMENT & REAL ESTATE NEWS

Bayshore became the dominant route only after the fairgrounds moved in the late 1970s.

That shift matters because it reframes the event. Gasparilla’s iconic images are not immutable traditions.

They are choices shaped by transportation, development and crowd management.

The Riverwalk changed one thing, not everything

Downtown’s Riverwalk has become a major gathering place, but its impact on Gasparilla is narrower than many assume.

“I don’t think it really has changed a whole lot,” Kite-Powell said of the parade route itself. “From the vantage point of the Riverwalk, you really can’t see much of the parade.”

Where it did matter was the invasion.

READ: Channelside Development & Real Estate News

“The spectatorship of the invasion has probably been increased quite a bit by the Riverwalk,” he said, noting improved access along the waterfront.

Crews as civic on-ramps

Gasparilla’s social structure may be its most enduring feature.

Many crews are now multigenerational, with third, fourth and even fifth generation members.

The largest growth came in the early 1990s, when all-women crews emerged and participation expanded rapidly.

By the mid to late 1990s, there were roughly 90 to 100 crews, a number that has remained relatively stable.

For newcomers, crews offer a way into Tampa’s civic life.

“Joining a crew can be a way to begin to engage in the civic and social life of Tampa,” Kite-Powell said.

The reputation and the reality

Gasparilla is known as a drinking holiday. Kite-Powell said the reality is more nuanced.

Public intoxication has become more visible since the mid-1980s, shaped by changing norms and image-driven culture.

The night parade has long carried that reputation. The day parade varies widely by location and timing.

“For your first Gasparilla experience, the kids parade is a great way to do it,” Kite-Powell said.

Geography matters too.

“Once you get into Hyde Park, it gets pretty rowdy,” he said. “Downtown’s even rowdier. The closer to the bay you can get, the better.”

A useful myth is still a myth

No subject draws more confusion than José Gaspar himself.

“It’s impossible to prove a negative,” Kite-Powell said. “But every effort to prove that he existed has come to a dead end.”

He does not believe Gaspar was a historical pirate. He believes the figure was fabricated to serve a purpose.

Even so, the impact is real.

The pirate story gave Tampa a shared ritual that stuck.

From floats to finance

One of the clearest changes over time is economic.

Early parades featured floats sponsored by local companies that used the event as a marketing stage.

Many of those businesses no longer exist or are no longer locally controlled.

“You just don’t see businesses like Publix used to have floats in the parade,” Kite-Powell said.

Corporate sponsorship now plays a larger role, driven by scale and cost.

“The parade is extraordinarily expensive,” he said. “To keep it a top-five biggest parade in the country, that takes money.”

That money sustains the event and also reshapes it, creating tension between access, tradition and spectacle.

Tampa’s pirate identity was built, not inherited

Gasparilla is not just a parade. It is a brand asset.

“The reason our football team is called the Buccaneers is because of Gasparilla,” Kite-Powell said.

From festivals to races to businesses, the pirate imagery signals Tampa long after the parade ends.

That identity was not accidental. It was staged, repeated and reinforced until it became real.

From the beginning, Gasparilla was a story told loudly enough and often enough to become part of Tampa’s philosophy.

And more than a century later, the city is still living inside it.

For more information on Gasparilla exhibits at the Tampa Bay History Center, click here. To learn more about the museum, click here.