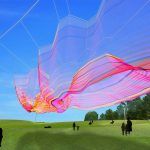

Janet Echelman, renowned across the globe for her aerial net sculptures, has finished her design of a new installation in the St. Petersburg Pier District. Her sculptures are known for transforming open spaces and creating inviting places where people can relax, reflect and enjoy nature.

Her installations have appeared around the world. Among them: the signature outdoor sculpture for the Gates Foundation in Seattle; an installation for the permanent collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., and a legacy sculpture for the Vancouver Winter Olympics in 2010. She has created 55 sculptures in 22 countries on five continents over the past 22 years.

Entertainer Oprah Winfrey once ranked Echelman’s work No. 1 on her “List of 50 Things That Make You Say Wow!” and Echelman was named an Architectural Digest Innovator for “changing the very essence of urban spaces.”

A native of the Tampa Bay area, Echelman grew up on Davis Islands and now lives in Boston. TBBW corresponded via email for this Q&A about her, her work and her life.

The theme of inclusivity seems important to you, why is that?

It’s important to me that my work is out in the public realm, often over the streets or walkways. When I installed a sculpture in Sydney, Australia, a man who lived on the street came up pushing a grocery cart. He asked me what the work was and shared with me what he thought. He might never have felt comfortable entering an art museum, so I loved that we could have that conversation. I place my art over the street because everybody feels entitled to be there. It’s like breathing air. I want my work to be as accessible and free as breathing air.

Bending Arc is the title of my sculpture for the St. Petersburg Pier, tying to a phrase that was used by Martin Luther King Jr. about how the moral arc of history is moving towards justice. That is a feeling that I also share.

You’ve traveled the world, what are some of your favorite destinations?

I have had the privilege to travel and study in so many countries around the world. The unique culture and urban spaces of each has inspired me and affected my art. I cannot choose one favorite since they are all so different and special in their own ways! I’ve found inspiration and beauty everywhere—from the ancient carved stone caves of Ellora in India, the immense stones of the Roman Coliseum in Italy, and the Ikat weavers in Indonesia, to China, where you may see the gesture of a master calligrapher brushing ink on rice paper, or a tall building going up with scaffolding made of bamboo.

How do you decide where you want to create a new installation?

Any new project my studio takes on must allow us to grow, explore and make our best work—that is the primary criteria I have for any new project. We receive inquiries from around the world—in rural and urban areas, public and private—and I find that working on projects in different scales and contexts keeps my brain working at different frequencies, which I believe leads to more interesting designs.

I seek to make artworks that create an energy in balance with each site—a combination of the right idea, the aesthetic form, optimal proportion and sequence of color that together speak to the preexisting site. It is never quick or easy. Even after years of experience, I still have to search for it every time, never knowing if it will come. It’s difficult and unpredictable. I suppose that is precisely why I love it, because it keeps me on my edge, always learning and pushing into the uncomfortable zone.

What’s the biggest challenge in your work?

When I started making art, my biggest challenge was learning to hear my inner voice and finding a way to notice and pay attention to my own ideas. I began writing and drawing with my nondominant hand, which gave me access to my more fledgling, vulnerable ideas that were being overpowered by my more conscious, skilled hand. Once I began to pay attention to these new ideas, the biggest hurdle was to learn how to respect them— the way to respect an idea is to invest the attention and work needed to develop it. This was difficult, but learning to do so was an important step in my growth as an artist.

When developing an idea, I remind myself not to start with compromise. I envision my ideal goal—what would result if I had no limits in resources, materials or permission. I’ve learned that eliminating options too soon is costly, because many ideas might be more viable than they initially appear. They just need a chance to mature and develop.

If you start with yourself and make sure that you fully believe that what you’re doing will create positive change in the world, then you can go out and share your vision with genuine belief. And being authentic is the most important thing when communicating about one’s art.

Can you describe your artistic process? Where do you find inspiration?

I look all around me for inspiration—at the forms of our planet in macro and micro scale, to the patterns of life within it, to the measurement of time, weather patterns or the paths created by fluid dynamics. I am always in search of inspiration from life. I guess this is my way of making sense of the world, and finding my tiny little moment within the larger unfolding story of humanity on our planet.

I always turn to the unique site as a guiding force for each artwork. When I make the first site visit, I get a feel for its space, talk to the people who use it, and spend time uncovering its history and texture to understand what it means to its people. I work with my colleagues to brainstorm, sketch and explore all ideas, without censoring our ideas in the early stages. As the sculpture designs begin to unfold, our studio architects, designers and model-makers collaborate with an external team of aeronautical and structural engineers, computer scientists, lighting designers, landscape architects, and city planners to bring my initial sketches into reality. We fabricate our artworks through a combination of hand-splicing and knotting together with industrial looms, and then install on location. It is a gradual, collaborative, and iterative process from every angle, and takes more than a year to go from idea to the final artwork.

What has been your proudest accomplishment as an artist?

Holding onto my artistic vision as I make tradeoffs to build larger and more permanent works—different from smaller, temporary sculptures. And for having integrated my personal life with my work life so that they enrich each other rather than compete. ♦